SimMayor stuurde ons een linkje naar de Red Hill Guide to CPU Choice, een errug kewle site met een historisch overzicht van de ontwikkeling van de x86 processor. Het verhaal begint bij het ontstaan van de hedendaagse beschaving in het jaar 971 van het vorige  millennium, toen Intel met de 4-bit 4004 de eerste microprocessor op de wereld bracht. Dit beestje draaide op een frequentie van 740KHz en bestond uit niet minder dan 2250 transistors. Nadat in 1974 de 8-bit 8008 was gereleased volgde in 1978 de 8086, de eerste x86 processor. Een minder dure variant met 8-bit bus werd in 1979 op de markt gezet. 1980 betekende een doorslaggevend jaar voor Intel. IBM gaf bij de ontwikkeling van de Personal Computer in eerste instantie de voorkeur aan de Motorola 68000, maar wegens een gebrek aan poen werd voor de goedkopere 8088 gekozen. De rest van het sprookje moge duidelijk zijn: de 286, 386 en 486 volgden in de loop der jaren en inmiddels zitten we hier met onze GHz Athlons en PIII's.

millennium, toen Intel met de 4-bit 4004 de eerste microprocessor op de wereld bracht. Dit beestje draaide op een frequentie van 740KHz en bestond uit niet minder dan 2250 transistors. Nadat in 1974 de 8-bit 8008 was gereleased volgde in 1978 de 8086, de eerste x86 processor. Een minder dure variant met 8-bit bus werd in 1979 op de markt gezet. 1980 betekende een doorslaggevend jaar voor Intel. IBM gaf bij de ontwikkeling van de Personal Computer in eerste instantie de voorkeur aan de Motorola 68000, maar wegens een gebrek aan poen werd voor de goedkopere 8088 gekozen. De rest van het sprookje moge duidelijk zijn: de 286, 386 en 486 volgden in de loop der jaren en inmiddels zitten we hier met onze GHz Athlons en PIII's.

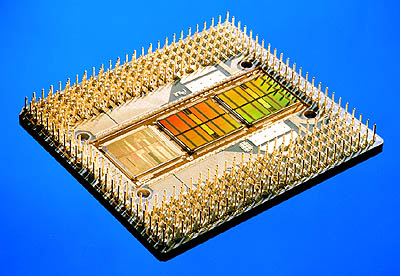

Degenen die al wat langer meelopen zullen bij het lezen van deze site ongetwijfeld met veel weemoed terug denken aan klassiekers zoals de 286-16, 386DX-40, 486DX/2-66, Pentium 75 en Pentium Pro. De PPro was vanwege z'n matige performance in 16-bit apps weliswaar geen groot succes, maar het feit dat de P6 core nog steeds wordt gebruikt geeft aan hoe revolutionair het design van de Klamath-, Covington-, Mendocino-, Katmai- en Coppermine (overgroot)pappa destijds moet zijn geweest:

Very difficult to speed-rate, as its 32-bit performance was good but its 16-bit performance was often slower than a standard Pentium, let alone the newer chips. The Pro was a physically massive chip, or, more accurately, two chips bonded together - the CPU itself and a 256k or 512k secondary cache chip too. The advantage of this is that the processor could access the cache RAM at full clock speed. The disadvantage is that it was big, hot and very expensive to produce - particularly as there was no way to test the wafers prior to bonding and a single tiny fault in either one of the two wafers meant Intel had to throw them both away. This reduced the yield and so increased the cost even more. The Pentium Pro wasn't quite been a failure, but it certainly was not a great success. There were four main reasons for this:

- It was much too expensive for normal use.

- It needed a non-standard (and expensive) Socket 8 motherboard.

- The sheer size of the chip meant that even Intel couldn't make very many of them without dramatically cutting Pentium production.

- It was optimised for 32-bit code. This was fine if you were running UNIX, OS/2 or Windows NT, but useless for the 90% of people who ran DOS/Windows or Windows 95. The Pro found a place in very large fileservers and graphics workstations, but was slower than a standard Pentium in normal use (i.e. for most DOS and Windows 95 users), and it was not compatible with the cheap, reliable Socket-7 motherboards used by the 6x86, 6x86MX, K5, K6, Pentium, Pentium MMX and C6.

Unlike all previous Intel X86 CPUs, the Pro (and the very similar Pentium II) has a RISC core. Intel, like NexGen with their pioneering Nx586 and AMD with their K-series CPUs, wrap a dirty old X86 interface around very high-speed RISC engine. The hard part, of course, is translating complex and illogical CISC instructions into a series of smaller, simpler RISC instructions. Most of the newer CISC CPUs are taking this approach now - but it's interesting to note that only the already obsolete AMD K5 has bettered the performance/clock speed ratio of the more traditional CISC-based Cyrix 6x86 family.

(It's worth mentioning that the Pro really should be listed as a sixth generation part. It is, after all, the same basic P6 engine as the Pentium II and Pentium III. We list it here because, like the Nx586, it had next-generation design with previous-generation performance. There are Pentium Pro fans out there who rave about its performance, but we have never quite understood this - in all our testing, the Pro has been clearly inferior to the 6x86-200, and no particular improvement over a Pentium 166. Still, they sold in tiny numbers, so perhaps we didn't get to see them at their best.)

The major strengths of the Pentium Pro were its very fast maths co-processor, the huge on-chip secondary cache, and the lack of a viable alternative for large server installations - the faster Pentium II, K6 and 6x86MX parts were not really designed for multi-processing, and the the old Pentium was already too slow. Although it failed on the desktop, Intel were able to salvage their investment by pushing the Pro into the cost-no-object workstation market, where it competed successfully against the small-volume, high-performance RISC chips: MIPS, PA-RISC, PowerPC, SPARC, and Alpha. In addition to the 200MHz version listed first, there were 150, 166 and 180MHz parts, and a range of cache sizes for the PP-200: 256k, 512k and 1Mb. These last were mega-expensive.

|

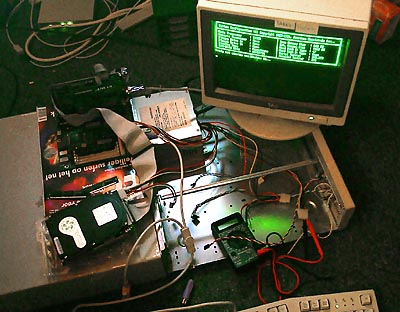

Die Red Hill jongens hebben een prachtig stukje geschiedschrijving in elkaar geklust dat verplichte kost is voor elke tweaker. Het deed bij mij in ieder geval een onbedwingbare behoefte ontstaan om oude spullen uit het stof te halen. Zie hieronder een paar pics van m'n 386SX/25 (lief klein chippie) met 8MB RAM, Hercules videokaartje (notabene van ATi) en een 106MB Seagate harddisk. Dat moederplankje had in 1992 nooit durven hopen dat-ie ooit nog eens 8Meg onder z'n hoede zou krijgen ![]() . De videokaart en monitor zijn trouwens afkomstig uit een Tulip Compact XT, ook al zo'n klassieker:

. De videokaart en monitor zijn trouwens afkomstig uit een Tulip Compact XT, ook al zo'n klassieker:

|